Woman overcomes adversity to make B.C. trades history

In 1981, Marcia Braundy made B.C. history.

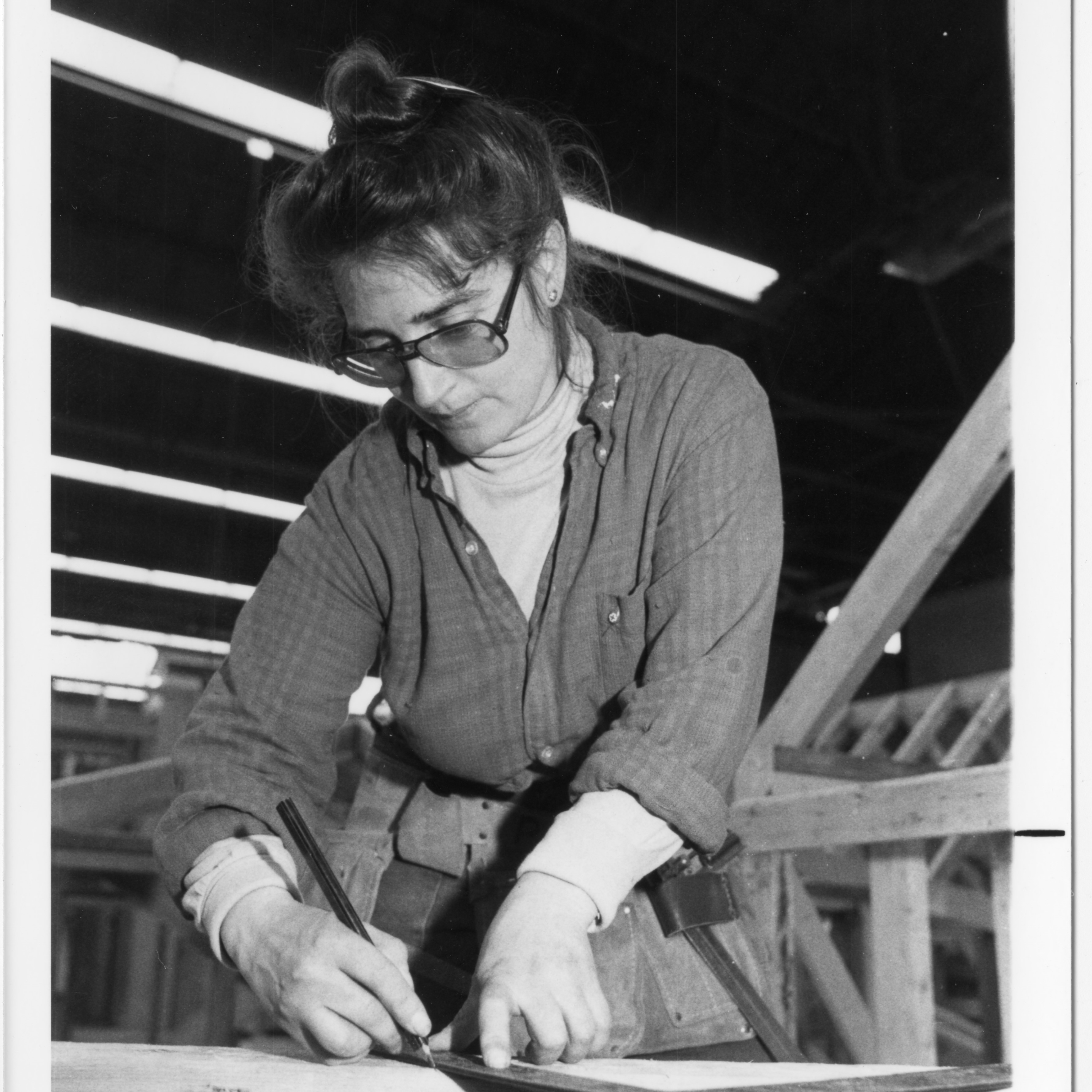

Feminist and activist Marcia Braundy practices roof framing at BCIT in 1981.

*Editor’s note: This article contains very strong language & describes graphic harassment

Marcia Braundy never planned to make history as B.C.’s first female Red Seal carpenter.

It was out of necessity. Things needed to be fixed and built. So she learned.

“I had Volkswagens in the 60s and I had to be able to fix them but I didn’t have work that paid me any real money,” she said. “I had to do all of that myself. I found wonderful men who would let me use their tools and give me direction if I needed it.”

She got so proficient that she was able to rebuild two entire engines.

Marcia’s main passions were feminism, environmentalism and alternative schooling. While organizing for the National Student Association in the U.S, she began to uncover a skillset that would be invaluable her whole life.

“Chuck Hollander, who hired me there, gave me the gift of learning what I am really good at in this world,” said Braundy. “I am a community organizer, and I am an activist, and I am really good at identifying issues and helping people find ways to solve them.”

Finding home in the valley

Born in Massachusetts and raised in Pleasantville, New York, Braundy’s travels eventually brought her to B.C.’s Slocan Valley.

“I knew immediately that this was my home,” she said.

She founded the Slocan Valley Free School, which still exists today as The Whole School, a community-supported, non-profit, independent, elementary school. Its program focuses on outdoor learning, multi-age, small class sizes, independent education planning, and student-driven learning.

In the early 1970s, an effort was made to build a community centre in the valley. But there was little money for the project, so residents rolled up their sleeves and got to work, including Braundy.

“I ran the volunteer crews and I would sit down once a week with someone who knew more than me,” said Braundy. “The men seemed busy most of the time but they would come and we would draw pictures on 2x10s of the work that needed to be done.”

Braundy and other women in the valley wanted to learn but soon found they were being sidelined by the men.

“I noticed that the guys kept taking the tools out of the women’s hands, saying ‘here, honey, let me show you how to do it’ and then they didn’t give the tool back,” she said. “So I started having women’s work days where we could come, teach each other and learn. It was wonderful.”

The centre eventually became the Vallican Whole Community Centre which still serves the region to this day.

Starting pre-apprenticeship training

After several years of working on the community centre, Braundy decided to learn more about carpentry to earn a better living. But after a year of asking the province’s apprenticeship counsellor in Nelson to get into pre-apprenticeship training, she had been ignored.

“At that point I called the director of apprenticeship,” she said. “And I said ‘I think I am being discriminated against and I am really unhappy.’”

She was told a course in Dawson Creek started in three days so she made her way to Northern Lights College. She very quickly found out that all of the other women who had tried to take training in the male-dominated programs had left.

“I heard about them every day and people would tell me women couldn’t make it here,” she said.

Despite these stories, made a promise to herself that no matter what, she would give four years of her life to becoming a carpenter.

“An apprenticeship was four years,” she said. “And whatever happened in that period of time, I would keep going. And if at the end of four years it was too icky, I gave myself permission to walk away.”

Things got icky fast. “Marcia’s tits” was scrawled on the blackboard, “Fuck you, miss” was on the tool room door and “Marcia’s potty seat” was written in the bathroom.

To keep herself motivated she would play song tapes recorded by her friends back in the valley and look at architectural plans of an upcoming Slocan Valley project on her wall.

“They were fabulous plans,” she said. “They had three octagonal bays on them. I had them on my wall because that was the job I was going to do when I got out of school. I had reasons to keep me there.”

Everyday she erased the crude messages on the blackboard in class but finally she called her instructor over and told him about the harassment. He erased the board and never said anything to anyone.

When the school was creating posters to welcome a local MLA, some of them were also adorned with crude messages or sexualized depictions of nude women. Braundy objected, telling her classmates that she would not let those images represent the carpenters.

“I grabbed a can of paint and threw it all over their poster. They picked up a can of paint and threw it all over me. I didn’t care. That poster wasn’t going up,” she said.

Braundy had been documenting all the harassment and misogyny on campus and after six months she decided it was time to take action with school officials.

“I have to speak up,” said Braundy. “I have to. And I did. I let them know what was happening and called it to attention.”

The result shocked her.

The college president, Barry Moore, went around to every single male dominated trades training classroom on campus and told them that their language and actions were inappropriate at an institution of higher learning and if it continued they would be thrown out of school and would not get an apprenticeship anywhere in British Columbia.

Getting experience

Braundy graduated with the highest grade in the class on her final exam and took her certificate back to the valley to begin her apprenticeship. She worked in various woodworking shops, helped with Nelson’s first Victorian renovation and did some homebuilding projects. But the real money and opportunity was in the carpenter’s union.

After months and months of being ignored she finally showed up to the union office and demanded a copy of the constitution and standard collective agreement. After she reviewed the documents with a lawyer and found nothing that would prevent her from becoming a member she showed up at the next meeting. She discovered that she had be accepted as the first woman member of B.C.’s carpenter’s union, local 2458.

Now a third-year apprentice, her first union job was the Chahko Miko Mall in Nelson and her business agent told her this: “Marcia, you don’t have to take any shit from anybody. You’re a union member now.”

Her crew was doing concrete flooring work and she made fast friends with the other workers. When she eventually left the job, the team threw her a party and gave her a 15-year-old bottle of rye whiskey in a velvet case.

While working on the Hume Hotel she became a miter joint expert, learning how to precisely chisel the joints so that even to this day they have stayed intact without cracking.

“There’s a pride that comes from doing the job that is thrilling,” said Braundy.

She soon found herself living in a work camp doing larger, more complex jobs. Braundy was part of a 70-person team doing form work on two side-by-side coal silos, each 278 feet tall. Day shifts were 13 hours and night shifts were 11 hours. Typically, carpenters would be paired up for long periods of time but the foreman bounced her from man to man. After 25 different partners, she learned the foreman wasn’t punishing her.

“Each of the guys that I was with there, it was the first time they had worked with a woman,” said Braundy. “And he wanted as many men there as possible to have that opportunity. I am forever thankful to him. I felt great on the site with all of them.”

But those good feelings were shattered when a crude joke began circulating the camp and was eventually told to her.

“I can say that I have no memory of exactly what the joke was, but I remember that I felt like I had been punched in the stomach and I couldn’t breathe,” said Braundy. “And I was horrified that all these people who I had thought were my friends had known about that joke and were walking around with that thought in their minds. I suppose I should have written it down, but it was so horrible and awful I just couldn’t even think of writing it down. I had to get through the rest of the day but I was barely functional.”

Her friend, a carpenter from Cranbrook, found her in her room crying and she made him promise to never tell anyone what he had seen. He agreed.

“I had to get up the next day, go to work and put all of that away,” she said.

Making history

In 1981, Braundy was in her fourth year of apprenticeship and traveled to BCIT to complete her trades education. She was met with more disturbing behaviour. Her classmates regularly posted explicit pornographic images on the classroom wall. When she finally brought it up with the instructor, he took the images down but never said anything to anyone.

On the last day of class, one of the students put a particularly explicit pornographic image on the back wall of the classroom and declared, “this is for the guys in the next class, we hope there aren’t any women in it.”

She quietly shredded the image, threw it in the trash and went to return her books as she prepared to take the final exam. She left her Frederickson Metric Square in the room. The carpenter’s square was designed by carpentry instructor Paul H. Frederickson to help builders, and he had signed Braundy’s. When she returned, it had been destroyed.

“My signed Frederickson square had been twisted into a knot and dropped on my desk,” said Braundy. “‘CUNT’ was written in pencil below it in big letters.”

Emotionally shattered, she began the half mile walk across campus to take the test that will determine if she will be a Red Seal carpenter or not. A classmate of her’s told her not to pay attention to the bully. She asked him one question: “Where were you when it was going on?”

She later found out the bully had failed his exam, but she had passed. She was informed by the school that she was the province’s first ever female Red Seal carpenter

The story doesn’t end there. Here projects are almost too numerous to mention. Braundy even worked with 13 other women to develop EMMA’s Jambrosia, a food manufacturing business to support chronically unemployed women in the West Kootenays.

In addition to to being on BCIT’s board of governors and holding PhD from University of British Columbia, Braundy is a community development worker, social change activist, independent research scholar, multimedia project manager, archivist, teacher, and was the founding national coordinator of Women in Trades and Technology National Network (WITTNN). She curates and manages KootenayFeminism.com and has been active in the Canadian women’s movement since 1972.

Braundy is currently building a freely-available, full-text digital archive of equity in apprenticeship and technical fields, with a focus on initiatives for under-represented groups.