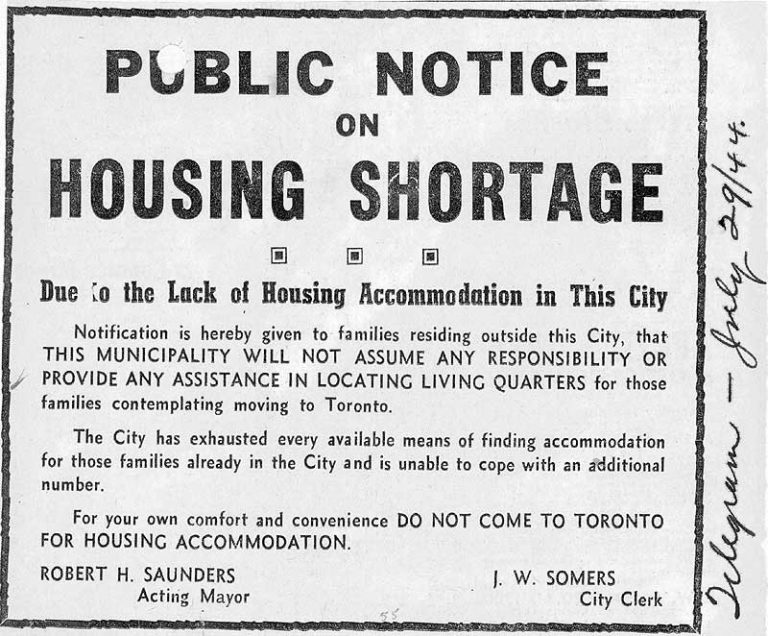

Wartime homes: why Canada is reviving an 80-year-old idea

During its day, the program divided officials on how much government should be involved in housing.

War workers’ homes were built as part of the WHL program in Winston Park, Ont. – City of Toronto Archives

Key Takeaways:

- Wartime Housing was a successful solution to rapidly supply housing to wartime workers and returning veterans.

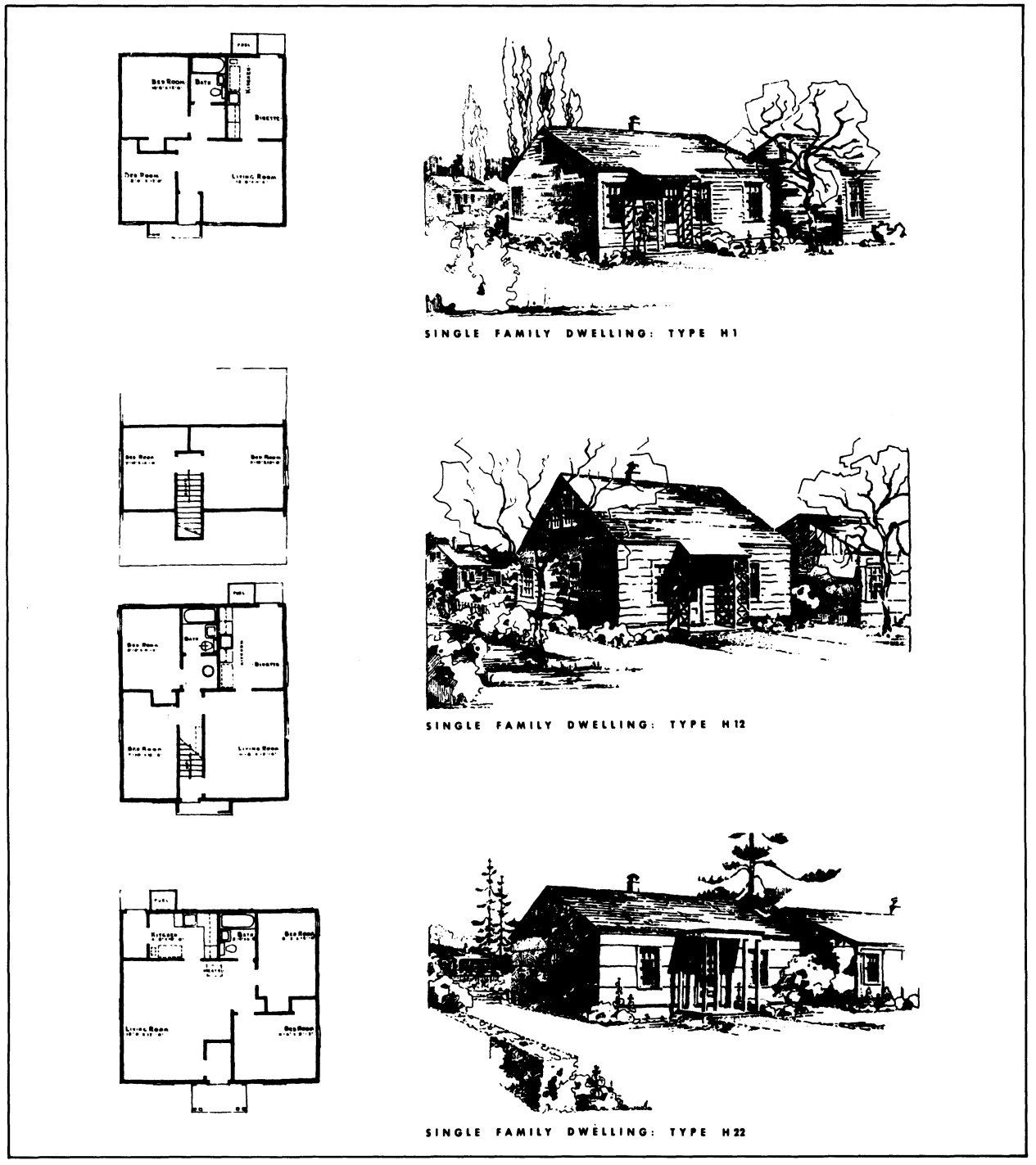

- The program used prefabrication and standardized designs to build thousands of rental homes.

- The controversy that ultimately led to the halting of the program had less to do with its methods and more to do with disagreements over the level of involvement the government should have in home construction and development.

The Whole Story:

The Government of Canada is reviving an old idea used during WWII to address critical housing shortages: developing a housing design catalogue.

Housing Minister Sean Fraser announced consultations will begin in early January 2024 on a housing design catalogue initiative.

The initiative’s goal is to accelerate the delivery of homes by standardizing housing designs, starting with low-rise construction. It will explore a potential catalogue to support higher density construction, such as mid-rise buildings, and different forms of housing construction, such as modular and prefabricated homes. The government will also look at ways to support municipalities, provinces and territories looking to implement their own housing design catalogues.

“In order to build more homes faster, we need to change how we build homes in Canada. We are going to take the idea of a housing catalogue which we used the last time Canada faced a housing crisis, and bring it into the 21st century,” said Fraser.

But if it was a good idea back then, what happened to to the original program and why was it stopped?

The late Jill Wade — a celebrated academic, author and researcher in B.C. — dove into the topic in 1980s for her paper “Wartime Housing Limited, 1941 – 1947: Canadian Housing Policy at the Crossroads” which was published in Urban History Review.

A familiar problem

According to Wade, home-building declined to a disastrous low in the early 1930s before starting a gradual pre-war recovery. Later, between 1942 and 1945, wartime scarcities in skilled labour and building materials resulted in another lag. An Advisory Committee on Reconstruction study, known as the Curtis report, suggested that current building shortages by 1945 would amount to 114,000 units. Wade boiled the crisis down to three main issues: deferred residential construction, overcrowding and doubling up, and substandard accommodation.

A new solution

This crisis led to the creation of Wartime Housing Limited (WHL) which was intended to be a temporary emergency effort to alleviate housing pressure for war workers and veterans. Wade wrote that between 1941 and 1947 WHL successfully built and managed 26,000 rental units, representing a directly interventionist approach to housing problems. Despite being a crown corporation, it functioned more like a large independent builder in the private sector than a federal housing agency.

WHL’s process was to first assessed housing needs in war industry areas. With Privy Council approval, it proceeded with construction, using land obtained through agreements with municipalities, expropriation from private owners, or federal land. Local architects and builders hired by WHL implemented war housing projects based on company designs and specifications. WHL had priority access to building materials from Munitions and Supply.

With a shortage of building materials and the need to build rapidly, WHL employed an inventive semi-prefabricated or “demountable” technique. Instead of using a fully prefabricated, WHL made standardized plywood floor, wall, roof, partition, and ceiling panels in a shop at the project location and erected and finished the house on site. Across Canada, the company used the same standard house types recognized as the “wartime house”.

Dismantling the program

Wade argued that the program demonstrated the federal government could efficiently meet social needs by participating in housing supply. And this wasn’t just hindsight. At the time, the Advisory Committee on Reconstruction recommended a national, comprehensive housing program emphasizing low-rental housing.

Here’s how WHL president Joe Pigott put it in 1945: “If the Federal Government has to go on building houses for soldiers’ families; if they have to enter the field of low cost housing which it is my opinion they will undoubtedly have to do, then there is a great deal to be said in favour of using the well-established and smoothly operating facilities of Wartime Housing to continue to plan and construct these projects and afterwards to manage and maintain them.”

He was no layman or outsider. Prior to his work at WHL, Pigott was a successful Hamilton contractor and the president of Pigott Construction, Canada’s largest privately owned construction company at the time, amassing more than $113,000,000 in business in a single year.

Instead of taking Pigott’s and others’ advice, the federal government initiated a post-war program promoting home ownership and private enterprise. Wade wrote that in doing so, officials “neglected long-range planning and low income housing”.

Eventually WHL was absorbed by Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CHMC) and dismantled. In addition, during the late 1940s, WHL’s stock of affordable housing was privatized.

“This market-oriented perspective hindered advances in postwar housing policy in the same way that, for decades, the poor law tradition blocked government acceptance of unemployment relief,” said Wade.

A clash of politics

While there were many factors that Wade believes contributed to the fall of the WHL, her analysis boiled it down to a fundamental view of how much involvement the government should or should not have in construction, development and housing.

Humphrey Carver, a senior executive at CMHC and a thought-leader during Canada’s post-war reconstruction efforts, stated that the “all too successful” wartime housing program “should have been redirected to the needs of low-income families,” but “the prospect of the federal government becoming landlord to even more than 40,000 families horrified a Liberal government that was dedicated to private enterprise and would do almost anything to avoid getting into a policy of public housing.”

Wade also cited Lawrence B. Smith, a housing specialist associated with the Fraser Institute, who explained that federal housing policy “sought to encourage the private sector rather than to replace it with direct government involvement.”

Wade’s research and writing highlights a fundamental question of the extent of government involvement in construction, development, and housing, a debate that continues to shape housing policies today.