Construction labour crunch continues as demand booms

This month we take a hard look at worker shortages and what can be done to address them.

Key Takeaways:

- Despite great efforts to grow the workforce, demand continues to outpace labour supply.

- Recruiters have developed new digital tools to try and connect workers with employers, but face-to-face relationship building remains critical.

- Contractors believe there needs to be a massive societal shift towards respecting trades careers and educating young people about the benefits the industry has.

- SiteNews spoke with contractors, academics, labour experts and recruiters to understand what is happening with Canada’s skilled labour shortage and where it’s headed.

The Whole Story:

The dark shadow of workforce shortages has long been looming over the Canadian construction sector. Now that it has hit, has it really been as dark as they said it would be? Is the construction sector finding ways to cope? What are experts doing to address the shortage? We spoke with labour experts, economists, recruiters and contractors to get their thoughts on the current state of things and what they think the solutions could be.

Demographic challenges continue

Times are tough but they are going to get tougher, say construction labour experts.

While few could predict that the COVID-19 pandemic would throw the sector into a new level of uncertainty, many believe it has accelerated trends that were already underway.

BuildForce Canada’s latest report and forecast explained that as Canada’s economy began to rebound in 2021, older workers were slow to come back.

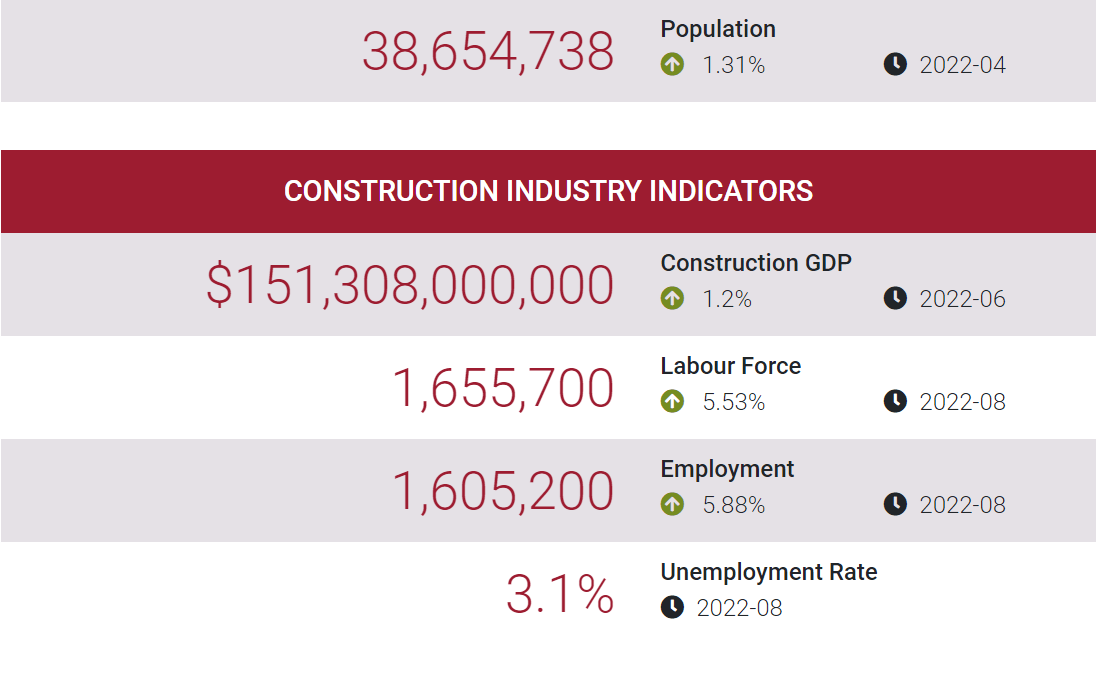

“If you look at the overall census data, 19 per cent of the population is over 65 and 20 per cent is between 50 and 64,” explained Bill Ferreira, BuildForce executive director. “And those under 16 only account for 16 per cent of the population. We have a demographic crunch. This is what we have been saying for ten years. The challenge the industry faces is not just an industry challenge, it’s a country-wide challenge. The population is getting older and not enough young people are not coming in adequately enough to meet the needs of the economy. More people are set to retire in the next 15 years than we can replace.”

Unlike the Great Recession, when younger workers were let go first and took longer to return to pre-recession levels of employment, the pandemic caused some older workers in the core working-age group to leave the labour force, many of whom have been slow to return as emergency measures were lifted.

BuildForce found that this caused a tightening of labour markets for most parts of the country and shoved unemployment rates lower as employment outpaced labour force growth for most of the year.

In addition, last year also saw a construction boom with total year-over-year construction investment rising 11 per cent.

Construction investment is essentially sustained into 2023 and then declines gradually over BuildForce’s six-year forecast period. The group expects total investment to be approximately 1 per cent lower by 2027 than levels posted in 2021.

Shortages likely to get worse

“In my opinion, the situation is likely to get even more challenging for the industry as it shifts into the mix of projects we are building,” said Ferreira. “When you look at the requirements for meeting some of the goals – admittedly aspirational goals – of government to double new homes over the next ten years, reduce greenhouse gas emissions for existing buildings, all that will require a shift in the workforce. This is particularly true for renovations to get existing buildings down to net zero. Requirements will increase. While technology will play some role and mitigate some challenges, it’s unlikely to mitigate all of those challenges. The requirements for labour are likely to increase, not decrease.”

The group estimates that construction demands will require the industry’s labour force to find 15,900 workers over the forecast period. When this demand growth is added to the 156,000 individuals expected to retire during this period – in total, approximately 13 per cent of the 2021 labour force – the overall industry recruitment requirement rises to 171,850 workers by 2027. BuildForce data shows that while the industry is expected to recruit approximately 142,850 new-entrant workers under the age of 30 during this period to help offset some of this requirement, even at these heightened levels of recruitment, the industry is likely to be short some 29,000 workers by 2027.

Ferreira noted that the federal government has introduced new supports for employers to help with costs and barriers to taking on apprentices. There are also programs that the government is looking at implementing to provide more incentives to those looking for new careers to choose essential industries like construction.

“The government is certainly doing its part in terms of helping employers recruit job seekers and young people,” said Ferreira. “Premiers have started to engage the federal government around immigration policy to see if there are reforms that could increase skilled trade workers coming into the industry. The federal government certainly seems open to these discussions.”

The issue is economy wide. Ferreira noted that the national unemployment rate is slightly above 5 per cent.

“When I was in my 30s, unemployment was 9 or 10 per cent,” he said. “To have 5 per cent is really unheard of. July was the lowest unemployment ever recorded since they started keeping track in 1976.”

The result has been some reluctance to bid on projects out of fear the labour won’t be available.

“This doesn’t mean projects won’t go forward,” said Ferreira. “They just maybe won’t go forward as quickly. The workforce is working harder today than ever before and employers are doing their very best to keep pace but the demands are outstripping the ability of the labour force.”

Changing perception

Chandos Construction, a nationwide contractor, is feeling the crunch.

“We have 740 employees at the company,” said Tim Coldwell, president of Chandos Construction. “If we could, I would hire 100 carpenters and labourers tomorrow and put them to work. The supply is not there.”

The company is also facing similar challenges for project managers, estimators, site superintendents and other roles that are often filled by those who start their careers in the trades. Coldwell believes part of the solution begins with a major perception change around the trades.

“Frankly, new grads coming out of high school are more interested in working for Google or Microsoft than for construction projects,” said Coldwell. “ The industry has this challenge around being seen as cold, dirty and messy. There’s a whole other side to that conversation.”

The shortage has pushed Chandos to be strategic about the jobs it takes and how much it takes to ensure its labour force is not overextended.

“The solution is kids,” said Coldwell. “You have to get to kids. It’s not good enough to get kids in high school.”

Coldwell explained that one of the big things that started the decline of trades careers was in the 1990s they took shop class out of most high schools in Canada and the U.S.

“That’s gone,” said Coldwell. “I think we need to get back to letting kids know about the virtues of trades work.”

Teaching children modern construction

He noted that research suggests children form their opinions about who they want to be and what they want to do when they are 6-10 years old.

“What you really need to do is get into the curriculum taught in schools for ages 6-10 and talk about construction and those careers being a good thing,” he said.

Provinces like Ontario are already doing this by introducing construction concepts to grade three students.

“When’s the last time you talked to a 13 year old who was excited about being a plumber or electrician or a parent that was excited about them doing that,” said Coldwell. “There are societal challenges that underpin this.”

Coldwell hopes that the new generations of youth understand that construction is a sector that uses tablets, 3D modeling, exoskeletons, robotics, AI and other cutting edge technology.

“The industry is transforming very quickly and the future of construction work will be less about shoveling in a pit and more about organizing tools and equipment, and thinking with your brain about how to use those supports on job sites,” he said. “I think kids particularly don’t know about that. They think they will be shoveling at the bottom of a trench in a snowstorm.”

He also wants young people to understand the financial security construction work can bring. A red seal carpenter in Toronto can make roughly 48 bucks an hour.

“That’s $100,000 a year,” he said. “With overtime it could be $120,000. If you start a trades program when you are 16 you could be pulling that when you are 20.”

There is also lots of opportunity for entrepreneurship. Coldwell noted that many tradespeople can start contracting businesses and make even more money.

Part of Chandos’ current strategy has been to target underrepresented groups like women and Indigenous people. They also are open to giving opportunities to struggling young people.

“If we could, I would hire 100 carpenters and labourers tomorrow and put them to work. The supply is not there.”

Tim Coldwell, Chandos Construction President

This is something Coldwell is passionate about, as he was once a 17-year-old heading down a dark path.

“I self-identified as an at-risk youth,” he said. “I was going to be in a cardboard box on the street. I found my second family and purpose in construction.”

Coldwell was hired by Chandos Construction where he now serves the president.

“If you give someone a chance, positive role models and a career that can pay $100,000 a year, so many kids would love that opportunity,” he said. “They are loyal and thankful and come to work happy and engaged. That flows to increased productivity and it’s a win all around.”

Recruiters adjust to assist employers

Workforce recruiters are becoming more sought after to help organizations fill construction positions.

Michael Scott, vice president of Impact Recruitment’s building division, explained how employee sourcing has evolved in the construction sector and what companies must do to compete for labour.

“It’s nothing new,” he said. “When I started this division 10 years ago we were just coming out of the global financial crisis, right when Vancouver construction was about to rebound properly. There was a labour crunch then.”

However, Scott explained that the past decade, construction has grown it to a far more prominent career as issues like affordable housing are at the forefront in people’s minds.

“Construction and development is now an industry that seems more viable – not just the trades. It’s purposeful,” he said.

While the world has changed in many ways over the past decade, some things remain the same.

“Technology is part of it, but when it comes down to it as a recruitment partner, construction still lives on shaking hands, meeting face to face and getting a gauge of who someone is – whether that’s a carpenter, labourer, electrical, mechanic, project manager or site superintendent,” explained Scott. “When we started the division ten years ago, we made a point of always meeting the person. That hasn’t changed.”

New technology and the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed the industry to become more familiar with digital tools like video calling. Scott says this allows recruiters to cast their net further and digitally meet more candidates. This also helps recruiters encourage clients to meet with candidates from other provinces.

Not all roles have been equally difficult to fill.

“Difficult roles to fill have been high expertise jobs like estimators and superintendents because most organizations would like to see a super who has built what that company builds. Looking for that super who’s built it from start to finish, from excavation on the ground to completion and handover is very difficult,” said Scott. “Other positions are senior project managers because if you are good at that, your organization is holding on to you and you are being fully utilized. It takes a while to get these people up the ranks. The other big one is just labour in general.”

This has led to many workers often getting multiple offers and then counter-offers when job hunting.

New tool aims to connect workers and companies

The rise in demand for recruiting assistance led to Impact creating AmbiMi, a skills-based job matching platform that combines an app with a human-centric network of job hubs to support job hunting and hiring. The technology helps filter and vet qualified candidates based on verified skills, while streamlining processes used in the traditional temporary recruitment agency model.

“We wanted to create a digital platform where workers have more direct access to employers,” said Scott. “We looked at it as a way for upward mobility of humankind, giving everyone the opportunity to upgrade their skill set.”

The tool has been released digitally in B.C. and will soon be available in Ontario. In the last few months the team has also begun setting up brick and mortar job hubs in B.C. and Ontario.

Scott encouraged employers who are searching for workers to have an open mind about someone’s background. While they may not have the exact experience you want, their experience may still be beneficial. He also stressed that interviews are critical, as it’s common for workers to get multiple offers.

“When you interview, give them the ultimate respect,” he said. “They made time to speak with you as an employer.”

He noted that even if that person is not a good fit, it is still important to keep them in your network for future opportunities.

Recent tightness demand-related

Some academics believe the recent labour crisis spike is more than demographics and the struggle it causes could be better for the industry in the long run.

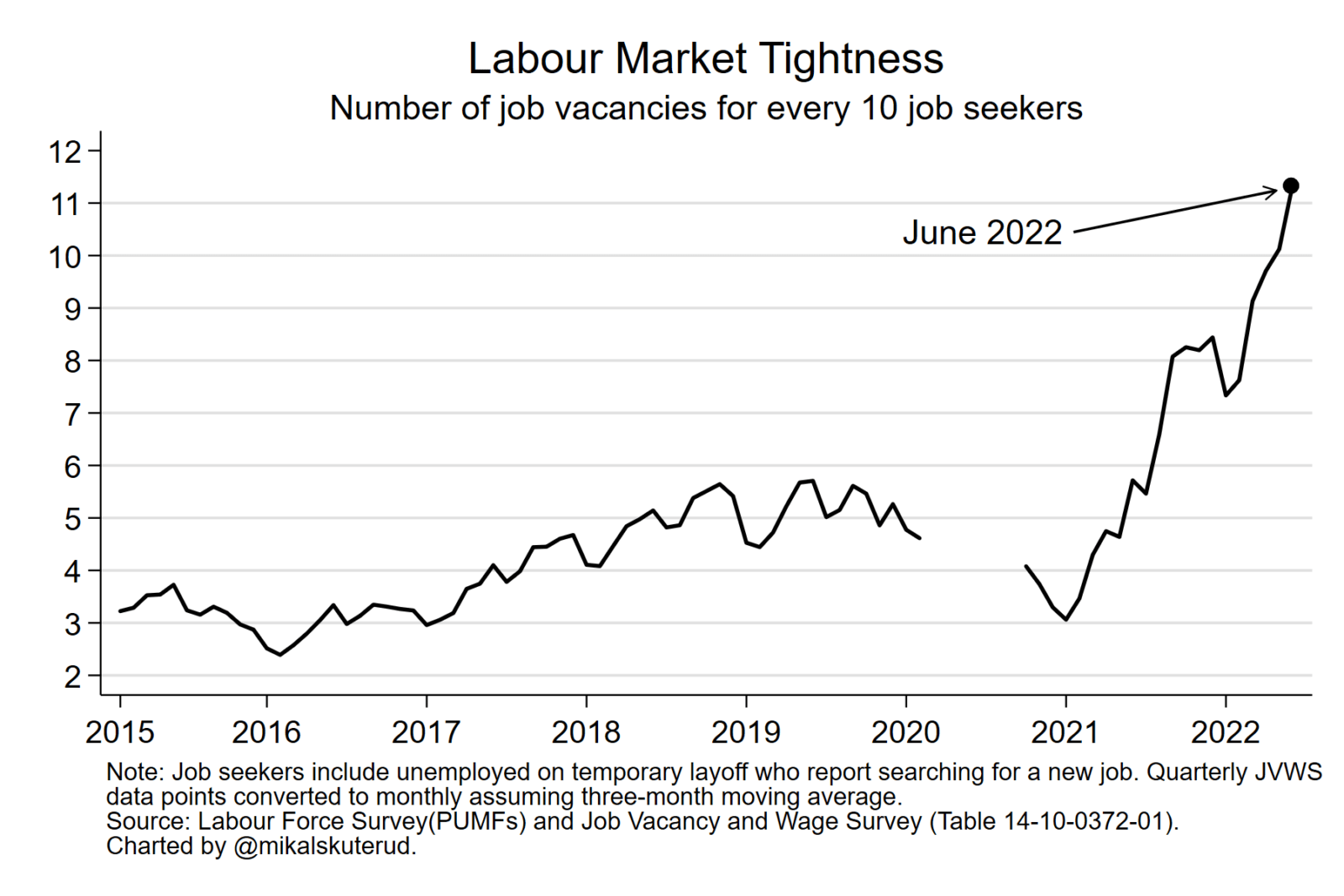

“My reading of the data is that the overwhelming market tightness is not a slow moving demographic trend, that’s part of it, but it’s mostly something that appears to be the effect of the pandemic,” said Mikal Skuterud, economics professor at the University of Waterloo and director for the Canadian Labour Economics Forum. “And it appears to be driven primarily by the demand side of labour markets and not supply. The aging population and people moving to retire – that is happening – but we’ve seen a massive spike in tightness.”

Skuterud explained that the spike began in 2021 when the number of job seekers remained barely moved but the number of vacancies shot up. Skuterud, believes at least one factor lies in the pandemic relief that flooded business.

“Business failure rates were down,” he said. “The government threw more than $100 billion into the wage subsidy program and more through the rental subsidy.”

Skuterud noted that the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy was more than the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Canada Recovery Benefit combined.

“There were lots of businesses that even without the pandemic, would have failed,” he said. “These are zombie businesses with razor thin margins, barely getting by. This caused lots of ‘labour hoarding’, as we call it, through this period.”

He noted that there is also just simply a lot of demand for things being produced by Canadian businesses which is reflected in consumer prices and inflation.

When zooming in specifically to construction, Skuterud said job vacancies have always been high, reflecting the transitory nature of the workforce as people move in and out of jobs fast. During the pandemic, construction saw high vacancy rates but was not hit as hard as other sectors, like food and accommodation.

Shortages could be healthier in the long-term

To address construction workforce shortages, Skuterud says immigration is a policy option many in the industry are lobbying for and new government regulations could relax restrictions for temporary foreign workers (TFWs) – an issue that he believes could become a major battleground for trade unions in the future.

He and other colleagues recently wrote a critique of softening restrictions on the TFW program, calling the crunch an opportunity for workers to get better wages and conditions, and employers to innovate.

“There is much to be said for letting these labour shortages play out,” he said. “When there is high unemployment we try to train workers and encourage them to compete for scarce jobs. When the tables are reversed and it’s not the jobs that are scarce, why don’t we force employers to be more competitive by making the jobs better?”

Skuterud said there is little incentive for innovation when one can access low-wage TFWs.

“One issue in construction is there isn’t a lot of oversight and if labour standards aren’t being met TFWs are ideal. Ultimately they want permanent residency and they recognize that to stay on that pathway they shouldn’t ruffle feathers.”

Overall, Skuterud believes that the economic forces of the shortage will boost wages and conditions for workers.

“I am not worried,” he said. “If you can’t survive, you should free up some of your current employees that are not at a profitable company and relocate them to other businesses where they are more productive. That’s a good thing and it’s how competitive economies should work.”

Measuring the crunch

Are the labour problems we face today unique to modern times? Answering that is nearly impossible. Skuterud explained that the way we measure labour tightness is fairly new. Supply side measurements are pretty consistent and go back to the 1970s. But measuring demand was only updated recently.

Modern, comparable demand-side data only goes back to 2015, meaning there are few lessons to be found in the past.

“Until the early 1990s we used to measure labour demand in the ‘Help Wanted’ section,” said Skuterud. “Statistics Canada would literally get newspapers and use big rulers to measure the column inches of job ads. For many years, that was the help wanted index. It’s not at all comparable.”

Do you have a comment on this story or is there a topic you want us to dig into? Don’t be shy. Contact our team at hello@readsitenews.com.